Homo Economicus or Homo Sapiens? Quo vadis, Economics?

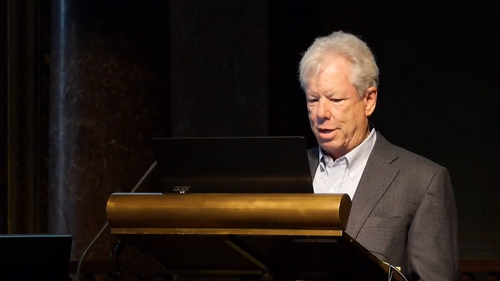

This year’s winner of the John von Neumann Award is Richard H. Thaler world-renowned professor of behavioral economics who held his inaugural lecture on the past, present and future of the field. Our summary comes with a commentary from Professor Péter Mihályi.

The John von Neumann Award has been conferred since 1995 to internationally recognized professionals who have contributed to the development of exact social sciences in an outstanding way. What is unique about the award is that it is granted by students, the members of the Rajk László College for Advanced Studies, Budapest. Among the former prize winners are Alvin E. Roth, Hal Varian, János Kornai and Daron Acemoglu.

Having obtained his doctorate from Rochester University, Richard H. Thaler is currently professor at the Chicago University. He is member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences as well as of the American Economic Association where he served as president until 2015. His principal research area is behavioral economics and finances, more particularly the psychological motivations behind decision making processes. Out of his six published books the most successful has been the joint publication with R. Sunstein Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness that uses the models of behavioral economics to explain everyday problems. Besides his books, his series of articles called Anomalies that featured on a regular basis between 1987 and 1990 in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, have received considerable attention.

In his inaugural lecture he proved through numerous examples that the neoclassical models of economics fail to describe reality accurately enough: the homo economicus does not behave like a genuine homo sapiens. Professor Thaler considers it the greatest strength of behavioural economics that rather than inventing bad psychology with bad models, it borrows some good psychology. In his vision formulated during the lecture, if mainstream economics is finally willing to incorporate the characteristics of human behaviour into its theoretical presumptions, behavioural economics as an independent school will eventually become superfluous and will cease to exist.

Please raise your hands if you are a homo economicus! – Professor Péter Mihályi’s reflections have been inspired by Richard H. Thaler’s lecture.

The lecture held at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences provided food for thought for several months for both professors and students. Just as in his articles and books, Thaler’s starting point was that the basic hypothesis of mainstream economics, according to which people as homo economici behave rationally, that is they maximize their utility and efforts and In doing so are capable of forecasting the future in an objective way, is false. Moreover, the lecturer went further to state that it is not adequate to presume that a large number of economic actors over a long period of time behave as if they were all homo economici (the latter assumption originates from Nobel prize winner Milton Friedman).

Thaler and I both believe that this new paradigm called behavioral economics will have incalculably far-reaching consequences. Most of the cases presented at the lecture were related to finances (stock exchange bubbles, price of real estate, pension scheme investments etc) , but it is easy to see that it would be high time to rewrite the standard textbooks of micro- and macroeconomics too.

As a Hungarian economist and lecturer of Corvinus University Budapest I would like to call the attention of students interested in the topic that all that Thaler wrote and said is close to the approach that our university’s internationally known and reputed (own) emeritus professor, János Kornai has developed over the last fifty years. Kornai in fact has gone even further than what we heard during the lecture. One of the main derivations coming from his train of thought is how important it is to clearly distinguish (or-or) routine-like economic decisions from rarely or never reoccurring decisions. As a consequence, for routine-like decisions (eg. daily shopping of a housewife) the assumption of strict rationality is admissible since this is how things work in real life. By contrast, irrational, emotional decisions are typical of decisions relating to major, personal decisions involving great value (eg. career choices, having a child) or huge-volume company or state investments (eg. constructing a nuclear plant, starting a war, backing a new invention).

Máté Baksa