Did it happen otherwise? What is true of the great historical narratives if viewed from a global perspective?

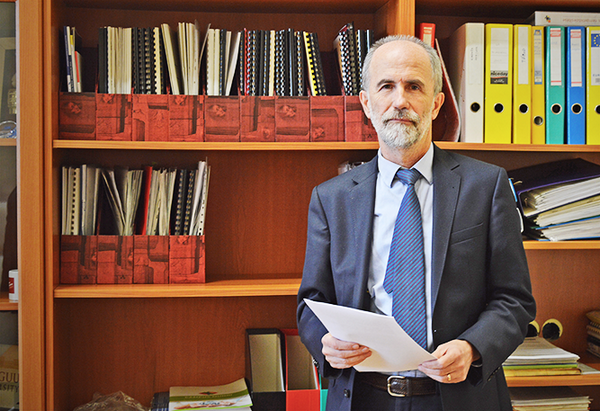

Our University hosted the European Network in Global and Universal History (ENIUGH) organization’s fifth European Congress in September. This outstanding professional event mobilized hundreds of scholars in global history from the best research and teaching centres of the world. Máté Baksa talked to Attila Melegh our university’s lecturer, chief organizer about the congress.

The Corvinus University of Budapest and the Central European University applied jointly for organizing the „5th European Congress on World and Global History” event, supported by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of History and the Hungarian Historical Society. With Nadia Al-Baghdadi and Judit Klement representing the other institutions, we operated a joint team of organizers. The lectures were grouped around the overall theme of Ruptures, Empires and Revolutions which offered some Hungarian scholars achieving increasing international reputation in the subject - among them historians, sociologists, political scientists and international relations experts - a unique opportunity to get involved in the international discourse.

What were the criteria in defining the programme of the conference? Who were the most important foreign and Hungarian participants and where did they come from?

The event was part of a series of congresses that had previously been held in Paris at the École Normale Supérieure and in London at the London School of Economics. This means that certain panels, programmes have been running for some time: the theme of the global history of forced labour, for instance, was featured at each of the congresses. What we meant as a novelty was to mobilize and involve East European research networks to a higher degree. We have partially succeeded as the number of Hungarian and Eastern European experts has considerably increased. Our attempt at attracting participants from the Middle East and Turkey, however, has unfortunately not been such a success mainly due to the collapse of the region and the unfavourable political situation respectively.

Which do you think were the most exciting public presentations and new themes of the conference?

One of the exciting themes was religion and revolution, which is very topical. In the course of history, religion has often played a role in radical political changes, moreover, some think about the French revolution as the religious struggle of reason. Another interesting reflection was on how we could view the history of socialism from a global perspective. In fact, it is a major error to view phenomena in blocks, in national silos. The characteristics of Socialism are sought to be understood through a particular bloc, through a particular country rather than by taking into account interactions with the global environment.

The Russian Revolution took place one hundred years ago in 1917. What is the message of these events for us? In what respect and how does knowledge on empires and revolutions help us nowadays?

Today we know much more, we see these past events more clearly. One of the important lessons learned is that behind each major society forming revolution there are very broad social sections– the Russian Revolution was also supported by huge masses, it was not a simple coup. Therefore we need to pay attention to situations in which mass discontent can lead to radicalization. This is relevant today as we seem to be facing an authoritarian cycle in several regions of the world. The situation needs to be viewed globally since although everyone mentions their own country, we see the political turning point as an overall trend from Russia through Turkey to Japan and India as well as numerous Western countries. In many respects the changes of global history are characterized by cycles and the current transformation can be interpreted as a counterpoint to the global economic and societal opening-up of the last thirty years. It is to be noted that the process has just begun and the outcome of the experiment cannot yet be seen.

How does a global approach to history facilitate the understanding of local and current historical events?

Global history is not the opposite of local history, but it rather integrates local interpretations and provides reference points for them. In my own field, it always upsets me when the high degree of outward migration from Hungary is mentioned. It is true that outward migration has increased considerably. Globally though, even within the region, the situation is far from being the worst in Hungary. To avoid interpreting events on an ideological basis it is useful to be aware of the global experience and context. The interpretation of history is very serious work, which is not limited to placing local histories beside each other. Right now, we are at the very beginning of this huge work, but world events will be radically reinterpreted if social conditions do not change.

As an example: the global history of forced labour is not only about the Gulag or slavery. There is the entire system of British and French penal camps, forced or semi-forced labour on the colonies when for instance Indian workers were transported to African construction sites. Or a later example: the Churchill government had concentration camps built in Kenya in the 1950-s. If these pieces are reinserted in the original story, our existing stories will not stand ground. We are facing unprecedented intellectual excitement and the current narratives will change fundamentally.

What is the significance of the fact that the Corvinus University of Budapest could be one of the hosts? What kind of co-operations, further research opportunities can be envisaged in connection with the theme of the conference?

As in previous years, the conference was preceded by a summer university for PhD students as well as a lecture series lasting a whole year. This helps attract young generations and local research communities. We intend to place the global perspective in the forefront of our educational programmes, the demand is clearly there on behalf of both the students and the lecturers. We should not lose this opportunity, especially not in Hungary where despite the size of the country, we tend to be inward-looking.

Organizing the conference has meant enormous work, in which we received a lot of help from the management of the university, from Dean Csicsmann, from the administrative staff and from the educational services of the university. We worked together with many colleagues and PhD students day and night. My special thanks go to my colleagues and students at Corvinus, Krisztina Gedó, Dorottya Mendly, Márton Hunyadi, Ildikó Juhász and Katalin Varga. They are fantastic people who I enjoyed working with.