What kind of world are we creating for ourselves with artificial intelligence? This is the most crucial question for the future.

The seminar series launched in March by the Corvinus Fintech Center presents the topics of AI and machine learning to the public. At the opening event Imre Bárd PhD candidate of the London School of Economics talked about the future of the regulation of AI. The series of events was opened by Márton Barta Strategic Director of our university, and the topic was introduced by Dr. Trinh Anh Tuan Head of the Corvinus Fintech Center.

Is artificial intelligence a blessing or a curse? Does it bring unprecedented freedom and well-being to humankind or to the contrary, unprecedented oppression and inequality? These questions can hardly be answered without being aware of how opportunities offered by advanced technology will affect our existing social systems. What is to transformed? What is to be regulated? How will rights and obligations apply to the different players in entirely new situations? Imre Bárd doctoral candidate of the London School of Economics focused on AI governance in his presentation of 1 March.

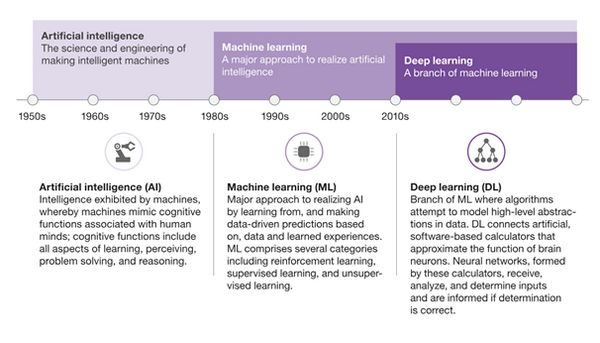

Although the expression “artificial intelligence” was coined by John McCarthy as early as in 1956, there is still no consensus on how we should understand it. (In its broadest sense it means technology that is capable of thinking and acting in a human or rational way.) While science might be owing us the precise definition of the term, the various attempts at defining it have brought us closer to understanding the meaning of intelligence. The AI paradox, for instance, sheds light on an exciting phenomenon: once a problem has been solved, there is no need for real intelligence to solve it again.

In his talk Imre Bárd presented the two types of AI: general AI that covers the entire spectrum of flexible and adaptable intelligence and specific AI that is only suitable for the solution of a well-defined problem. The most progressive technology seems to be deep learning that relies on the application of neural networks. Deep learning is a branch of machine learning in which AI is taught certain patterns that it will be able to recognize later on its own as a result of having been fed several thousand or million datapoints. Algorithms try to learn the high-level abstractions hidden in the data (which in the case of neural networks amounts to several internal/hierarchic layers). This training process can be implemented in different ways, the most important factor being the quality of the input. AI can only recognize the right patterns if the data fed to it is appropriate.

In the last few years, we have read perplexing news about AI technology. Cambridge Analytica obtained the data of millions of Facebook users without their consent and then used them to influence the outcome of the US elections. IBM Watson recommended wrong treatments to cancer patients. Researchers at Stanford developed an algorithm that is capable of detecting a person’s sexual orientation with high accuracy on the basis of photos. Some decision-support AIs have turned out to have racial bias and so on.

The above examples are all linked to situations where the application of artificial intelligence raised serious problems. Imre Bárd thinks that in order to avoid such situations as well as to abide by the principles of fairness, transparency and accountability, social regulation of AI is needed.

Just as human decisions may be severely affected by distortions of perception, this might also become relevant for AI. Since in the case of machine learning decision mechanisms are developed on the basis of data, it is vital to make sure that the data fed to the system are of high quality. The representativeness of the population should be ensured as well as its exemption from hidden human bias. In this sense artificial intelligence is the mirror of human thinking and society: the stereotypes inherent in our decisions are unconsciously transferred to the machines.

The principle of transparency serves a dual purpose in regulating AI. It can help us understand the basis on which AI took the decision, but it can also help prevent the establishment of data collection and processing monopolies that would pose a fatal threat to human freedom and autonomous decisions.

Whereas currently available AIs are capable of taking decisions based on pre-learned mechanisms, they are for the time being unable to explain the reason of their decisions in a manner that is understandable to humans. If they are to be entrusted with decisions affecting our destinies, we need to understand the logical bases thereof. In fact, a number of developers are working on AIs that are already capable of providing explanation models to their decision mechanisms. These, however, have not been finalized.

The excessive data mass and the huge data processing capacities raise the spectre of “transparent people”. As Yuval Harari Noah wrote, humans themselves will become hackable. If certain states or major companies are able to collect a sufficient quantity of data on us, the resulting connections and patterns might reveal things that we ourselves might not be aware of. Being in the possession of such knowledge, they can easily manipulate our decisions. Imre Bárd considers the EU’s GDPR to be a positive regulation as it calls ordinary people’s attention to the fact that their data are valuable and they have the right to know who processes them, how and why.

One of the most sensitive points of AI regulation seems to be accountability. Who might be held responsible for any damage caused by AI? Who can be forced to remedy them? These issues are not only exciting from a legal point of view. Legislation models our social values in an imperfect way, answering these questions is therefore partly a moral and value judgment task.

The changes brought about by AI can also be perceived on the labour market. The current trends are expected to continue: more and more jobs will be taken over by machines and server robots from humans. This might create serious social tensions that we should get prepared to address. At the same time changes on the labour market make it possible and necessary to question some of our premises, to rethink the social role of work or the principles of distributing wealth.

Apparently, it is vital to regulate new situations arising from AI: the options range from “hard” legislation through “softer” industrial standards to voluntary corporate guidelines. Developers and lawmakers should prepare for new situations together, the handling of which requires previous attempts. The so-called “legislative playgrounds” representing a protected environment for both the developers and the lawmakers seem to be good initiatives to help come up with joint social and technological solutions over time.

In Imre Bárd’s view, AI governance is primarily not about regulating artificial intelligence, but rather about regulating a world in which artificial intelligence is ubiquitous. We should find out what kind of world we wish to create through it. This is the most important question for the future.

Máté Baksa